food insecurity by the numbers

by Kelsey Adams

THIS PIECE WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN PRINT IN DECEMBER 2020, IN ISSUE TWO

The exorbitant price of frozen deep-fried chicken at a grocery store in James Bay, an Indigenous community in Northern Ontario. Photo courtesy Danielle Da Silva.

To be food insecure means a lot more than not knowing where you’ll get your next meal. Food insecurity is linked to a number of social, economic and racial factors that exacerbate issues of access.

It’s an injustice that anyone has to experience food insecurity. To live without constant access to healthy food is a setback that keeps people oppressed, alienated and othered. Most agricultural economies in the world produce a surplus of food—in a just, idyllic world, no one would go hungry.

That is not the case in our society.

Earlier this year, in March, The Globe and Mail reported that over 4.4 million Canadians feel food insecure due to financial constraints. That’s about one in every eight households in Canada. That includes 1.2 million children. Food insecurity can be anything from being worried about not having enough money for groceries to having to skip meals to be able to afford rent. Sixty-five percent of respondents came from working households, meaning even working people are struggling to feed themselves.

The study, conducted by PROOF, the University of Toronto’s food insecurity research centre, didn’t include data from some vulnerable populations like First Nations families living on reserve, homeless people and people living in remote northern regions. Meaning the numbers are actually much higher for the entire population.

One researcher Valerie Tasaruk stated: “One year of living in a severely food insecure household is associated with nine years less of life.”

health impacts of food insecurity

Food insecurity is a public health problem, affecting physical, mental and social health. Food-insecure adults are more vulnerable to chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes and mood disorders. Because food insecurity is linked to financial strain, people who experience it also have to choose between paying for food, rent or medication.

Exposure to severe food insecurity affects the wellbeing of children leading to asthma, depression and suicidal ideation in adolescence and early adulthood.

the different ways food insecurity impacts people's health

where race and ethnicity come into play

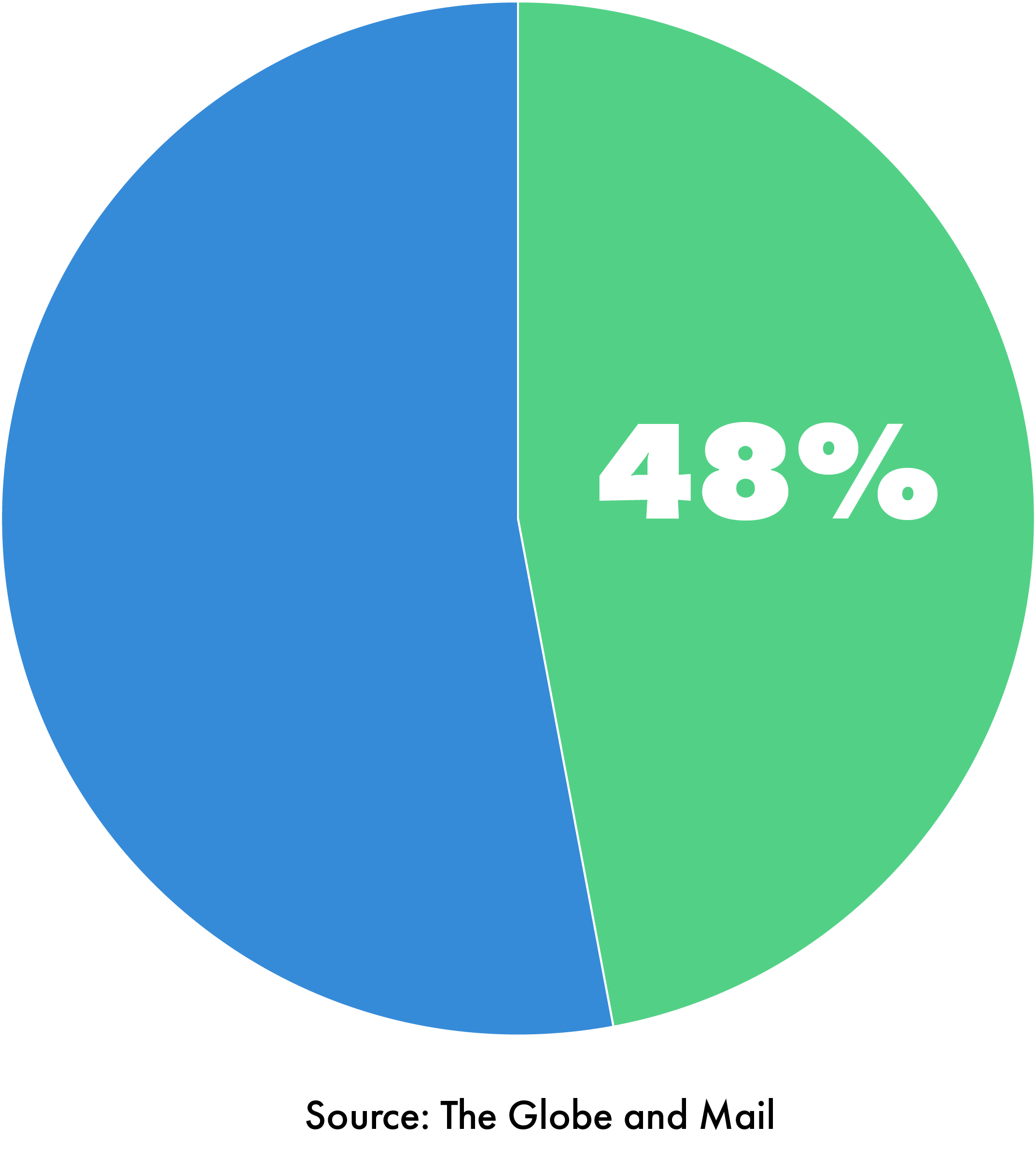

One in eight Canadian families experience food insecurity but one in every two First Nations households do. In November 2019, a decade-long study by the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment was released. The report was the first comprehensive look into the diets and nutrition patterns of Indigenous populations. Higher prices for food in rural and northern communities makes it increasingly difficult to feed a family of four fresh and nutritious food. Boil water advisories on many reserves also means access to clean, drinkable water is a concern.

The inability to hunt, farm and fish in traditional ways (because of government-imposed restrictions) also adds to a dependence on overpriced grocery stores.

48% of First Nations families struggle to put food on the table

A survey conducted by the Daily Bread Food Bank in Toronto found that 24 percent of respondents identified as Black, whereas Black people only account for eight percent of Toronto’s population. Poverty is the root cause of food insecurity and Black residents of Toronto are disproportionately impacted by poverty, more likely to be among the working poor, live in lower-income neighbourhoods and to have lower incomes.

Research suggests that anti-Black racism, over-policing, precarious employment and psychological stress contribute to higher rates of food insecurity. Black communities have higher rates of asthma and diabetes and worse health and educational outcomes overall. It’s not because of any innate biological pre-conditions.

We’ve always known racism kills, but we must remember it does so in myriad ways.

comparing the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity by race

and then comes...COVID-19

The PROOF report represents the highest-ever national estimate for food insecurity, and it was released before the pandemic.

This is clearly a long-stemming, endemic issue. With labour as precarious as it's ever been, businesses closing, people being laid off and the boost of the Canadian Emergency Relief Benefit waning, things look a little bleak. In April, the Daily Bread Food Bank saw a 53 percent increase in users.

But as humans do in times of crisis, the community came together.

Charities and community organizations filled the gaps caused by overwhelmed food banks that were running with half the staff due to social distancing restrictions. In south Scarborough, the Scarborough Food Security Initiative was launched after the local food bank closed, leaving hundreds of regular clients without anywhere to go. According to leaders, the food bank that closed served 248 families in social housing regularly. By April 4, their new organization was already serving more than 600 families and demand is still steady.

Throughout Toronto community fridges have popped up on the Danforth, in Little Italy and in Regent Park and other neighbourhoods. They’re maintained, sanitized and refilled by community volunteers and open for anyone to access whenever they need.

In this time of isolation and precarity we cannot forget that we must prioritize the collective over the individual. Watch out for all your neighbours. Give in any way you can—give your money, your food, your time, your compassion.